Including everything from psychoacoustics and sound topology to neural networks and philosophy of language, Florian Hecker has lately been setting up installations and performances internationally. Even though his work may appear as diligent, academic studies into various sonic materials Hecker doesn’t subscribe to an actual notion of research. Instead, his practice should be seen, he says, as a highly subjective and personal process – an act of artistic investigation that goes beyond objectified methodology.

From a quick glance at Florian Hecker’s discography one would be tempted to categorize his output as avant-garde, electronic music. But despite his close collaborations with for instance Russel Haswell, and a number of releases on Editions Mego and Rephlex, Hecker is constantly seeking to push the experimental aspects of his current projects beyond the strictly musical while finding still new spaces for presenting them “What I’m doing is a kind of experimentation. And the word experiment or experimentalist is fair to use. In many cases gallery or museu spaces or spaces that are not normally meant to function as places for sound or music are some of the last rooms for real experimentation possible”, Hecker reflects. “So when playing something in the concert hall you’re often dealing with preinstalled systems, preinstalled formats. Although more places now have surround setups, then surround is still a very defined thing again. It’s 5.1 to 16.4 – all these regulated numberings – why not try 7.n or something a bit more odd?!”.

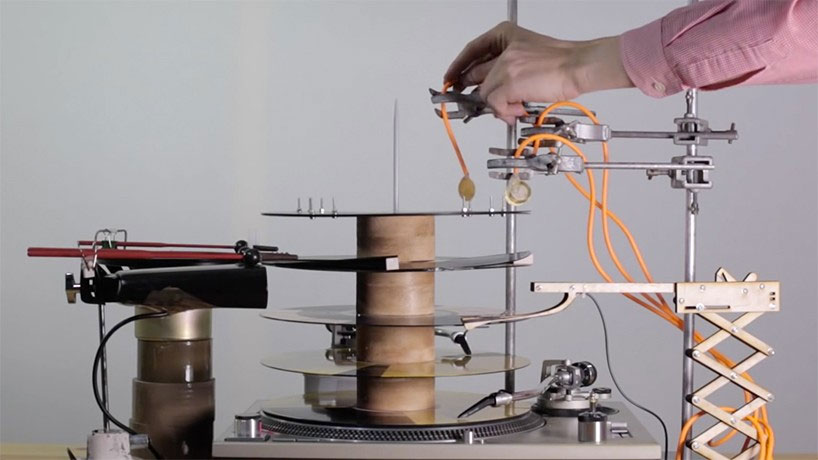

Florian Hecker, Untitled (F.A.N.N.); (2006-2013)

Installation View, Systemics #2: As we may think (or, the next world library), Kunsthal Aarhus, 21 September – 31 December 2013. Courtesy of the artist, Sadie Coles HQ London and Galerie Neu, Berlin. Photography: Jens Møller

Floating basis and Chimerized voices

Hecker explains this to us during our meeting in the basement conference room of Kunsthal Aarhus in Denmark – an almost 100 year’s old exhibition space that currently functions as a progressive centre for contemporary art of all sorts. Here Hecker is preparing a new commission for the Kunsthal’s SYSTEMICS series, a programme of exhibitions that explore the coming together of disciplines informed by cybernetic thinking. His contribution to this exhibition (as is also the case with his participation in MoMA’s is based on original sonic material. And c “Looking at my own practice almost from the beginning the situation has been, for instance when doing gigs with other artists that were published on Editions Mego, that there never was the stability of an actual platform. I was shifting from doing something in a night club or at a festival for improvised music, doing something in an academic contects or in a gallery space: It always fluctuated. And it still does. There’s not just one steady platform for it. Sound has different forms of existence and different variations, and so something is better for a record, while something else gets manifested in an installation piece”, explains Hecker. the manifold meanings of sound. One of his most ambitious works in this regard is Chimerization; a piece that was primarily developed for last year’s documenta exhibition in Kassel, but which has since been released as both an album (Editions Mego, 2012) and included in a book containing detailed visual documentation of several of Hecker’s pieces (Primary Information, 2013): “ “Soundings” – the museum’s first major sound art presentation) acoustics of most galleries and museums are not fit for sound works at all, Hecker seems to ontrary to the common complaint that the embrace this as a creative possibility – as an obvious invitation to extend conventional ‘sound art’ and music aesthetics. Overall, his career has been characterized by this kind of openness toward genres and working with sound: As a former student of Computational Linguistics, Psycholinguistics and Fine Arts, Hecker is deeply interested in In Chimerization what interested me was the sort of gap between the voice and the non-voice. What is happening between two different entities of sound? The piece was basically an intensification of three works I did beforehand. All concerning a topological twisting of sound material. In almost 90% of my other pieces the notion of synthesis and a sort of modernist take on how to generate sound is often the point of departure. Chimerization, on the opposite, was rather concrete in that it was about taking a recorded sound and looking at idea of quality changes in the transfer from one sound to the other”, Hecker says. This process of transferring and transposing applied as well to the relation between text, voice and sound. A central figure in the making of Chimerization was the Iranian philosopher Reza Negarestani, as Hecker explains: “I was introduced to Rezas writing through Robin Mackay , editor of the Collapse journal [independent journal of philosophy], and I had wanted to do a text/sound piece for quite some time. I was interested to work with an original thinker. Someone who is producing his own point of view on things, and not a secondary commentator. I consider Reza to be a great experimentalist, as well as a philosopher and a novelist, he is blurring many of the disciplines. And we have discussed a number things concerning signal processing, psychoacoustic background of the piece, and the scenario, the actual sites of recording – in this case, it was anechoic chambers.” With this specific collaborative project Hecker also deliberately distanced himself from a genealogy of earlier voice-sound experiments like, for instance, the field of sound morphing which had its heyday in 1980s in an institutional setting such as IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique): “I’ve never been convinced when I heard sound morphing examples such as the sound of a flute transforming into the sound of a voice. I was convinced that something was missing. At some point I had a meeting with Brian Moore, an expert in psychoacoustics from Cambridge UK, and author of the seminal book Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing, which was my first introduction to that particular field of science. It’s a technical book, and it’s concise and very detailed, but I believe that in many of the technical books addressing sound there’s like something written between the lines giving you more information than just the technical facts about a certain process. You find it as well in the writings of Curtis Roads for instance, in his considerations on microsound. In many academic writings I think there is a certain subtext culturally and coded which is telling many other things than just the ‘information’”, Hecker says.

The technical dimensions of sound

His double interest in both the psychology of hearing, i.e. the human experience of sound, and the purely technical understanding of sound processing and production has played a significant role in some of his latest work. Not only in pieces such as Hecker explains further: “When you shift your perspective toward the technical side of sound you suddenly have these measures and scales that can describe a sound very distinctly. In a piece called “Magnitude Estimation” (2010) I wanted through such scales to comment on decibel, and loudness. As such it’s a narration of 36 loudness values, a voice reciting various sound pressure levels. And what is happening is that with this 2-channel piece including 2 loudspeakers, one in each side of the gallery space, you will hear the actual sound level being described in the recitation, a kind of induction of the audience. In a similar way, Hecker explains, the text part of Chimerization included a sort of transparency between voice and word, respectively, as this related to the individuals reciting the libretto: “In the German version , the speaker is Guerino Mazzola who is a pioneer in music informatics and topological thinking on sound. It includes also the Argentine philosopher Gabriel Catren in the English version. So there are definitely some of these aspects in the piece concerning that the people whose work is being brought up, as part of a discussion, are actually the voices who are reciting the it.”, says Hecker. Representing Hecker’s current transdisciplinary work, Chimerization also points toward an aesthetic strategy that is not merely limited to abstract sonic experimentation but includes both textual and visual elements. He explains: “Depicting of a sound piece, i.e. through installation photography, is of course not adressing the sonic experience as such – at the same time, such visual documention can be highly suggestive and establish a particular perspective, says Hecker who in relation to these sorts of questions, met up with Antonio Torralba, an MIT-professor in artificial intelligence, vision and perception systems: “Together with some colleagues Torralba developed an algorithm which is – speaking dangerously simplified – taking certain qualities of one image and maps them onto the other. This is used a lot in making panoramic images, for example, through so-called auto stitching algorithms. And with these techniques I was able to produce a kind of in-between image of the two which I found it a good way to re-address photography or pictures for this particular project, in which the transfer of qualities and swapping of features has a special role” This work resulted in a Chimerization-book that came out in May on Primary Information, and which Hecker himself characterizes as a “high-modernist children’s book of 300 pages and with 500 images.” However Hecker’s point of departure has never been to explore the audiovisual as such, even though there is a strong visual side to some of his works: “Of course, in that way, my production is not sound works in a purely modernistic sense. And between 1998-2001, when doing performances, there were waves of audiovisual collaborations. I’m not really into that sort of combination, often it seems like a commodification of the experience in a given space. The dis-jointing or sequencing of a multitude of constellations, stimuli, objects appeals to me much more”, says Hecker.

Transdisciplinarity

The idea of connecting uneven material and practices has also been the focus of Hecker’s most recent work for the SYSTEMICS series at Kunsthal Aarhus. Hecker’s participation in SYSTEMICS #2 is yet another manifestation of his interest in combining or positioning sonic material with other art forms. As such he considers the past decade’s increase in sound art entering fancy gallery spaces to be mostly a question of labelling rather than the need for and an actual interest in sound: ”I’m really not in favour of this coinage. I think it’s pulling back, narrowing down discourse, the connections to other pieces. So I would much prefer that constellations of works in an exhibition come from anything and anywhere. Like a well curated music festival where it’s interesting to perform along other artists, that are not associated to your own practice.” Even though the Systemics Series contains several works that deal with sound as basic material, this was not the primary reason for Hecker’s initial contact with the artistic director of the Kunsthal, curator and writer Joasia Krysa. Rather it sprung from a shared interest in both machine algorithms related to human creativity and ideas of systems as such, whether expressed through sound based works or any other kind of material. And their common enthusiasm for these topics was, not least, represented by the Finnish artist and pioneer inventor of electronic instruments, Erkki Kurenniemi, whom Krysa had also been investigating intensively: “At some point Tommi Keränen, an artist and programmer from Helsinki, told me that Kurenniemi had spent a decade looking into neural networks, and we visited Erkki to consult him. Later Tommi went back to meet with him and he got some feedback on his design of the algorithm. Then, knowing Kurenniemi and his work for many years through my friends in Helsinki, I was really happy to see how prominently his work was reinstalled last summer at documenta (13)”, Hecker explains, referring also to Krysa, who was the person responsible for Kurenniemis inclusion in the important documenta exhibition that takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany. was not the primary reason for Hecker’s initial contact with the artistic director of the Kunsthal, curator and writer.

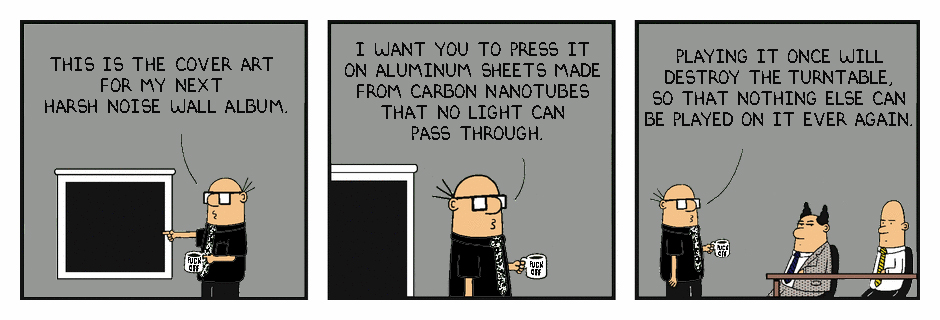

Neural networks and the shifting of virtousity

Relating to both Hecker’s and Krysa’s general occupation with systems and algorithms, Hecker’s most recent work for Kunsthal Aarhus draws upon his earlier interest in the relationship between sound and artificial neural networks. This revolves, among other things, around a new updated instrument consisting of custom written software and new sound material partly produced locally during a research stay in the city of Aarhus. For Hecker the interest in artificial neural networks has several starting points. He explains: “Some years ago I’ve was looking a lot into particularly Iannis Xenakis and some works he did late in his life. Concerning his use of Dynamic Stochastic Synthesis, this revealed a process that I’ve been using in many many pieces since 2001 onward, and which I still use. And basically this sort of work made me to look into non-linear ways of sound synthesis. I never could befriend myself with Cagean ideas of chance or aleatoric systems in music, so the idea of the artificial neural network that could create some ongoing instability or change into a system was something I felt very attracted to.” Hecker’s occupation with randomness and aleatorics stems also from another key figure of sonic experimentalism, the late David Tudor: “For this occasion [the Systemics #2] I’ve been looking into something like an actualisation or an upgrade of what David Tudor did with his Neural Synthesis piece from 1993. That’s a very late piece for Tudor, but I’ve always loved Tudor’s electronic music pieces, and this one particularly”, he says and explains in detail: “Neural Synthesis comes as a double cd box set, with one cd as virtual or binaural which provides a very specieal head phone listening experience while the other cd is a stereo mix with different takes of this piece. When reading the liner notes of this work there is this mention of usage of artificial neural networks in connection to Tudor’s instruments. And a really interesting thing here is the common attribute of Tudor as a “virtuoso”. He was Cage’s first choice as a collaborator on many pieces, including he story of how Cage came across him as being the only person that was playing the piano well enough to play a certain Boulez piano piece in New York. But with Neural Synthesis and the involvement of an artificial neural network, the decision making processes of the virtuous artist related to compositonal structure undergoes a great kind of complication; when then the machine is given an important role in decision making, the idea of virtuosity is challenged. Tommi Keränen created a system that accessed some of the instruments and synthesis tools i am using most, and connects these to an artificial neural network, which then will structures the piece in Aarhus”, Hecker says and points out that, according to this approach, lots of ideas of virtuosity can be shifted into other fields of practice through systemic processes. Given his very thorough considerations on the technical side of sonic experience – the apparatus, the instrument, the speaker, etc. – discussing such issues with Hecker seems easily to be able to go on for hours. The conversation comes to an end with Hecker needing to catch his train for yet another destination, most likely in order to uphold and maintain his current, intense output. His last remark lets us know, as well, that this has not forced him into producing audience friendly, electronic listening pieces. On the contrary, he says: ”the more alienating the better. What I want to do is to bring in non-linear functions into my works. And my primary concerns here are the complexified timbral structures, they create. Not in order to make it more accessible but simply to intensify the experience”.

Facts

Florian Hecker was born in 1975 in Augsburg, Germany. In his sound installations and live performances, he deals with specific compositional developments of post-war modernity, electro- acoustic music, and other, non-musical disciplines. He dramatizes space, time and self- perception in his sonic works by isolating specific auditory events in their singularity, thus stretching the boundaries of their materialization. Their objectual autonomy is exposed while simultaneously evoking sensations, memories, and associations in an immersive intensity. Hecker’s new work will be presented at the exhibition Systemics #2: As we may think (or, the next world library) at Kunsthal Aarhus, 20 September-31 December 2013, in conjunction with an artist talk and round table discussion. Florian Hecker’s work is commisioned by Kunsthal Aarhus in partnership with Goethe-Institut Dänemark. For more details and to follow development of the project see: http://www.kunsthalaarhus.dk .

Thomas Bjørnsten & Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek