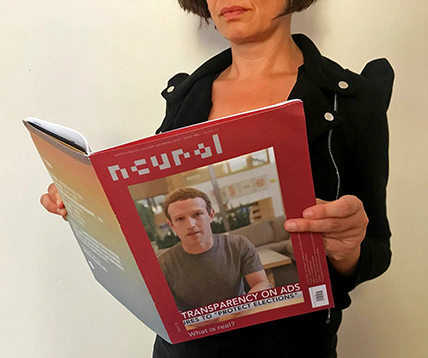

Sometimes the online world reveals unsuspected parallel dimensions. This is an unknown restyle of Neural independently (and secretly as we never knew about it) made by NY-based Motion and Graphic Designer, Clarke Blackham. Very nicely made, perhaps only a bit glossier for the magazine’s line, it testifies once more how even your most familiar outcomes can have another life somewhere else.

- 3D

- 3D printing

- 8 bit

- 8-bit aesthetics

- abstract

- abstraction

- acousmatic

- acoustic

- acoustic space

- acoustic/digital

- activism

- acusmatica

- aesthetics

- algorithm

- algorithms

- ambient

- analogue

- analogue sounds

- analogue to digital

- animation

- anonymity

- aound

- archeology

- architecture

- archive

- art

- art hack

- art rock

- artificial intelligence

- artificial life

- audio art

- audio recording and reproduction

- audio surround

- audio-video

- audio-visuals

- auditory culture

- bastard pop

- bend toys

- big data

- bio-art

- bioart

- biological

- bioluminescence

- biopolitics

- biotech

- black culture

- blockchain

- Blu-Ray/DVD + book

- bodies

- book

- book + other media

- booklet

- books

- bookshop

- breakcore

- broadcast

- brutalism

- capitalism

- Carsten Nicolai

- cd + dvd

- cd or other portable media

- cd+dvd video

- China

- cinema

- cinematic arts

- circuit bending

- classical/contemporary

- climate change

- cloud

- clubbing scenes

- code

- communication

- communication strategies

- computation

- Computational Arts

- computer art

- computer games

- computer music

- computer science

- computer voice

- computer-generated comics

- computing

- contemporary art

- copyright

- cosmotechnics

- counterculture

- criticism

- culture jamming

- cyberculture

- cyberfeminism

- cybernetic music

- dark ambient

- data

- data dating

- deepfake

- Deleuze

- demoscene

- design

- digital

- digital art

- digital culture

- digital economy

- digital sculpture

- digitalisation

- DIY

- djing

- drone

- dub

- dvd &/or dvd video

- dvd video

- dystopian

- ecology

- economy

- electro

- electroacoustic music

- electronic art

- electronic dance

- electronic literature

- electronic music

- electronica

- electronics

- electropop

- elettroacustica

- emusic

- ethnic

- exhibition

- experimental

- experimental music

- extra

- fake

- feminism

- festival

- fetishization of the offline

- field recording

- field recordings

- floppy disk

- Fluxus

- folktronica

- free form

- free pdf

- future

- Futurism

- game

- game engine

- gamelan music

- games

- geek culture

- generative

- glitch

- glitch'n'cuts

- global communication

- graphic design

- hacking

- hacktivism

- home devices

- identity

- idm

- images

- impro

- industrial

- information technology

- infrastructure

- installation

- installations

- interactive

- interactive sounds

- interfaces

- internet

- internet art

- internet-based art

- invisible networks

- kinetic

- language

- laptop

- late-capitalism

- light

- literature

- live performances

- machine learning

- machines

- magazine

- maker

- mashup

- media

- media archaeology

- media archeology

- memory

- microsound

- minimal

- mixed-media

- mobile

- modern classical

- multiculturalism

- music

- musica concreta

- musica informatica

- Musique Concrète

- neo-materalism

- net

- net art

- network

- neural

- neural network

- neural networks

- neuroscience

- new classic

- new classical

- new issue

- new media

- new media archeology

- new media art

- NFT

- NFTs

- noise

- noisy

- non-music

- obsolescence

- obsolete techniques

- out-of-body experience

- performance

- performing art

- photography

- plagiarism

- playlist

- plunderphonics

- politics

- porno

- post digital

- post human

- post rock

- post-digital economy

- post–techno

- preservation

- print-only publication

- privacy

- programmazione algoritmica

- psichedelia

- psicoacustica

- psychoacoustics

- psychogeography

- public infrastructure

- public space

- publishing

- pulsar synthesis

- radio

- radio and communication

- radio waves

- radio-art

- remote execution

- Reports

- retro aesthetic

- reverse engineering

- robot

- sci

- science

- science fiction

- security

- simulation

- site-specific

- social history

- social media

- social mythologies

- social network

- society

- software

- sonification

- sound

- sound and vision

- sound art

- sound poetry

- sound sculpture

- sound sculptures

- sounds

- soundscape

- soundscapes

- space

- spoken word

- stereoscopic vision

- street art

- subcultures

- surveillance

- synth music

- synth-disco

- techno

- techno-pop

- techno-social imaginaries

- technology

- technoscience

- telepresence

- text-sound composition

- theatre

- theory

- tokens

- Transmediale

- turntablism

- tv

- USB drive

- utopia

- vide

- video

- video art

- video games

- videogame

- virtual reality

- visual

- visual media

- visual poetry

- vjing

- voice

- wearable

- web

- webapp

- WiFi

- working online

- zine

Projects

- Sonic Genoma

- Suoni Futuri Digitali

- Wicked Style

- nordiC (Dissonanze)

- Tecnologie di Liberazione (2001)

- Virtual Light (1995)

- Internet Underground Guide (1995)

Colophon

- Chief Editor

- Alessandro Ludovico

- Assistant editor

- Aurelio Cianciotta Mendizza

- Contributors

- Josephine Bosma Chiara Ciociola Daphne Dragona Matteo Marangoni Rachel O'Dwyer Paolo Pedercini Paul Prudence Benedetta Sabatini

- Special Projects

- Ivan Iusco

- Chiara Ciociola

- Title Poet

- Nat Muller

- English Copyediting

- Rachel O'Dwyer

- Translations

- Giuseppe Santoiemma

- Advertising & PR Manager

- Benedetta Sabatini

- Production Manager and Digital Archivist

- Cristina Piga

- Technical consulting

- Paolo Mangraviti

Friends