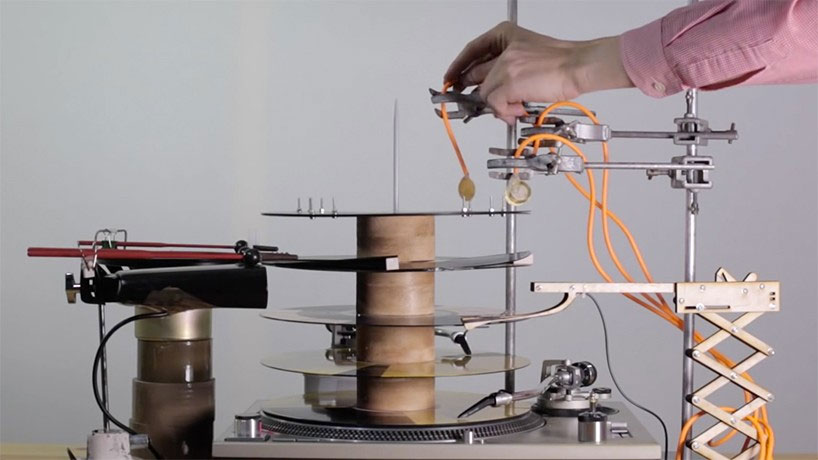

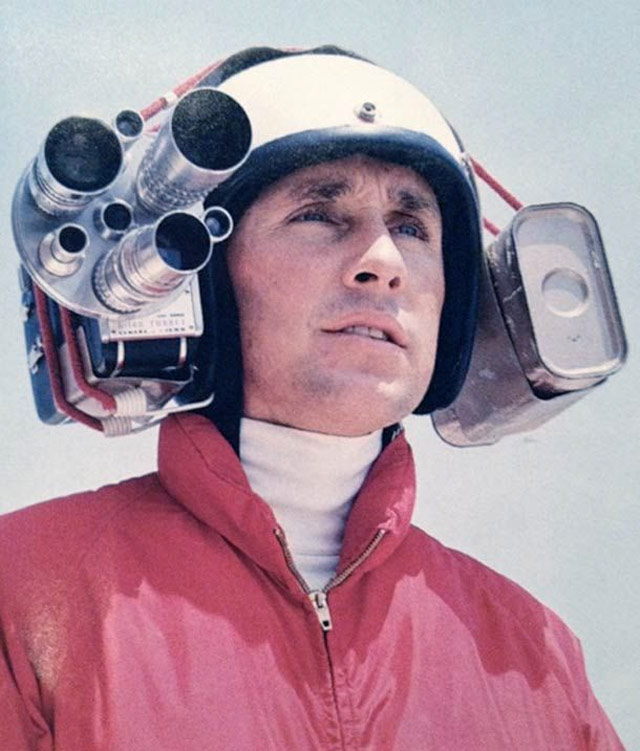

During the last edition of Transmediale festival in Berlin, the foyer of HKW was occupied by numerous theodolite scopes and data viewers, used to reveal to the audience different correlations of data. The graphs, charts and measurements presented and supported by an altered and unaltered metrological infrastructure offered information about the venue, the city of Berlin, the web and the festival itself, but in a rather unforeseen way. Users would be caught by surprise when first encountering the screens of the installation. Why would the level of noise at the HKW café need to be correlated to the numbers of likes of the Facebook Transmediale page? What does the light level of the building have to do with the Bitcoin currency rate? With a purposeful confusion that of course would leave no space for identifying any patterns, the technological sculpture Critical Infrastructure aimed to raise questions about our datafied present and our quantified lives.

In the following interview, Jamie Allen talks about the overall concept of the project that he developed along with David Gauthier during a three month artistic research and production residency in Berlin.

Daphne Dragona: You describe your latest work, Critical Infrastructure, as a ‘media-technical landscape survey’ which allows direct observation of a particular datascape – in this case, the festival- and a revelation of its materials and systems. Tell us a bit about the idea behind the project. What did you decide to measure, visualise and correlate? And how did the work interact with the other activities within the space?

Jamie Allen: The project is a commission and residency, and so the final piece came out of lots of talking and thinking about the themes already in discussion in and around the festival. Transmediale’s theme this year was ‘afterglow’, a concept that refers to the post-digital — the remains of a networked and digital culture that somehow came crashing down on us over more recent years. Mostly people think about “post”-whatever as a temporal shift, something that delineates historical, cultural thinking as having been surpassed in some way. And this can become a bit of a silly exercise of ‘era-making’, but there’s something to it, as well. So we tried to imagine ways of doing a kind of media archeology of the present, a way of examining the current ‘layers’ of the post-digital that can be made detectable ‘beneath our feet.’

The particular measurements selected show different scales or layers of infrastructure that support the Transmediale festival, and this supposedly auspicious notion of “digital culture” more generally. There are straightforward things that come to mind, like the power consumption of parts of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt cultural building, or the number of ‘Likes’ on Transmediale’s Facebook account. Beyond that, we wound up making a kind of parallel point about the amount and accuracy of this type of data. That is, we used data like “The Number of Views of the Most Popular Video on YouTube (Gangnam Style)”, which is, as of this writing 1,913,296,796. Now, that number is both cognitively and likely analytically entirely meaningless. How is it collected? I don’t see the number rise by one when I watch the video one time, so what the hell is happening there? And what could it possibly be feeding into, or used for? Why do “we” create it, maintain it? So some of our infrastructural data was wildly arbitrary, pointing at the ridiculousness of quantification and our general human propensity towards measuring everything, all the time, for its own sake.

D.D.: Critical infrastructure is definitely a very topical title. In an era that everything is being captured and quantified, still not much is widely known about the algorithms and infrastructures behind this increasing datafication. What can critical infrastructures offer? How does the term follow / add to critical making, critical design and critical engineering?

J.A.: There are two or three principle critiques being levied by the system. The first is that the digital infrastructures we have built are just ridiculous at some level; the vast majority of the data we generate, process, graph and store is driven not by its meaningfulness, but by other (very human) fetishes and anxieties. Another critique — one that commonly lies at the heart of the modes of making that you refer to (critical making, critical engineering, critical design) — is to acknowledge the rather ignored material and social and political layers that lie “beneath” “application” or “content” focused media and communications systems. Thirdly, the word “critical” helps us get around the sense that the use of the technological is always progressivist, or positive punditry. As Nam June Paik said, “I use technology in order to hate it more properly.” So Critical Infrastructure is derogatory of infrastructures by creating an infrastructure. Viewed in a certain way its similar to humanities pursuits like “Critical Studies,” which is critical of language, in language, by creating more language. Exploring or using a technology doesn’t mean you are “for it,” or enjoy it even. So the project creates a kind of an over-coded and superfluous additional infrastructure, that shows its properties, its fragility, more sensibly to us all.

D.D.: ‘Let s make data into a verb: to data’ you wrote as part of your statement for the context of your project. And it makes sense as not only do we constantly generate data but we also tend to more and more make sense through data, be it our habits, the urban life or our social interactions. Bur what do we do when it becomes too much? And most importantly, is there still some room for opposition, disruption or dismeasure?

J.A.: This “too much,” as the excesses of a supposed “information overload” actually seems a bit senseless, or contradictory, to me. Everything we are producing as data is produced by systems we ourselves create. Anyone who’s developed technologies will attest to the very human investment of meaning and intention that goes on. So there’s a balance of sorts, and we’re very good at adapting. It becomes a question of “how” we wish adapt, that’s all — it’s going to happen. Generally speaking human consciousness is probably a lot more capable and adaptable to these things than we give it credit for. There a story about how worried people were that train travel was going to mess up your brain because of all of the visual speed and ocular noise that rapid travel introduced… But people adjust; they create new tools, and make sense as you say.

The other kind of “too much” is a problem but of a more practical and immediate variety — creating far too many storehouses and streams of data than are worth having or that can be used effectively for good sense and change making. So, as arguments about all technology and technological development should go, the question shouldn’t be of thresholds (“too much”) or binaries (“should we have it at all”) but of types, aptness and tendencies (“if we’re going to have this, how should it happen, and who should be in control?”). This is where disruption and corruption can and should occur, which is where a non-fundamentalist and critically-empowered systems thinking is evolving. All systems are designed — mathematical, digital, economic — so we can redesign them in ways that express the right values and principles. Thankfully there seem to be a lot of strands of this kind of work evolving, inside and outside “art and technology” world(s).

D.D: Your installation was the outcome of a three month residency in Berlin which also included the organization of three workshops. Their titles, Leakage – Surveyance- Conveyance, very much sound as a call for awareness, as an invite to people to understand structures and apparatuses in order to possibly and ultimately provoke changes. Do you consider this as a counter-gesture, a move towards the use of counter-apparatuses? How did it affect the formation of your final project?

J.A.: Our workshops and the festival piece itself were indeed for counter-discourses about infrastructures and data. Transmediale is actually quite a rare community in this way, where peoples’ approaches are quite critical and thoughtful (this is not true of most digital culture and digital arts festivals, conferences or contexts). So our project serves as a backdrop for a number of strands of these kinds of discussions (The tripods reference the geology of media, the system as a whole creates a kind of “big data” system for the festival, etc.). Critical Infrastructure did well at installing these ideas in the festival venue and bridging to the conference themes — creating an observatory of realtime layers of ongoing infrastructure as well as gesturing back to the agelessness of these tendencies (through the use of ‘surveying’ equipment). There’s also an intentional link to Institutional Criticism (as an artistic practice or movement) that was also there, as there were some hard facts about the festival that were exposed through the data we presented (employee salaries, web statistics, etc.). These were not that salacious, but the kind of thing that gets people thinking about what they are implicated in, by participating in or being at Transmediale.

The installation was intentionally made to present information without drawing too many conclusions. A more explicitly activist or geopolitical invitation, a real counter-apparatus that you could use for something, wasn’t there. We thought about this a lot during the project’s development, as this is definitely something worthy of finding ways of communicating and doing. It is even something that the context of Transmediale needs much more of, honestly. The fact that such an invitation wasn’t part of Critical Infrastructure hopefully allows more room for personal interpretation and reflection, and also sets the stage for other projects that will allow for more direct, less “poetic,” looks at the repercussions and causes of techno-material infrastructures.

D.D.:Do you see yourselves working more towards this direction in the near future? And what do you actually think of this emerging scene of art engaging more and more with the materiality of the networks?

J.A.: There are definitely sociologies and anthropologies of infrastructures to talk about and investigate in different ways. Whether or not this takes shape into an “art scene” or not isn’t so important, I don’t think. But there is definitely something in the air (and in the ground, and in the oceans, etc.), and it is nice to get together to find out what it is with other people. Aside from the general disappointment with weightless and cyber-theoretical promises of the late-20th Century, the material craziness of our telecommunications activity on earth — like how we have extracted all the copper on the planet only to put it back into the ground again — is becoming more and more present. These systems that lie beneath all of our concerns about big data, net-neutrality, copyright and privacy help ground our digital utopias. These historically contingent and power-laden complexes of matter we call technologies, are difficult to contain and comprehend, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try…

http://criticalinfrastructure.cc/

photo credit:

01 – 02 Daniel-Rakosi, 03 – 05 – 06 Elena-Vasilkova, 04 Rebecca-Torp