[This is a talk presented at the Game Culture conference in Novi Sad]

Italy has a strong political tradition, having also generated various related creative movements wisely mixing politics and art (like free radio in the seventies, the luther blisset movement in the nineties the telestreet one in the two thousands and so on). Rejecting the usual parody scheme, Molleindustria has established a sort of paradigm in defining political hacktivism embedded into a funny and ironical video game system. He uses video game rules to foster ideologies, and in his unique case the software reveals how politics can be argued within classic ‘point and click’ interaction, making high score on rising personal awareness. His aesthetic and attitude have found their way in targeting the singular conscience lost in the overcrowded mediascape.

Political videogames in Italy.

Videogames have always been a controversial topic in Italy. From the late seventies there’s always been a moralistic current of thought opposing the use of videogames by young people. I’d like to cite just two of the most recent episodes. According to the Italian national newspaper La Repubblica, the Italian Minister of Justice, Mr. Clemente Mastella, has recently claimed that it would be advisable to create an “authority” that would “decide on acceptable standards related to the modalities of sale” of videogames, so that it might be possible to “find those (videogames) that contain unacceptable levels of violence”. The hypocrisy of the parliament is well coupled by the Catholic Church one, that has always opposed videogames and their dubious morality. One of the most active and young Catholic sociologist, Carlo Climati, has recently written a popular book containing an essay claiming that violent videogames can easily lead to satanist practices. In this scenario, the political use of videogames is quite natural, but it has really started only in late nineties. In 1998 the most famous leftist hip hop group 99 Posse, published a new album named ‘Corto Circuito’ (Short Circuit) that had a bonus ROM track containing a simple videogame. It consisted of a space invaders parody where the policemen were the aliens and they had to face a group of protestors shooting molotovs. The videogame rised loud protests from the right wing politicians, as an instigator to street violence, and they asked in the parliament to seize the product all aver, but the cd album was sold in 180.000 copies without any restriction. A few years later, a young Italian Flash programmer decided to dedicate time and energies to develop critical videogames, with funny, cartoonish characters, first focused to support the rising flexworker movement from a creative perspective. His name is Paolo, but he’s commonly known with his ‘firm’ name: Molleindustria, that is a contradiction in terms, meaning ‘flabby’ industry. Actually he’s a researcher and lives abroad, but let’s start from the beginning in 2003.

1. Work

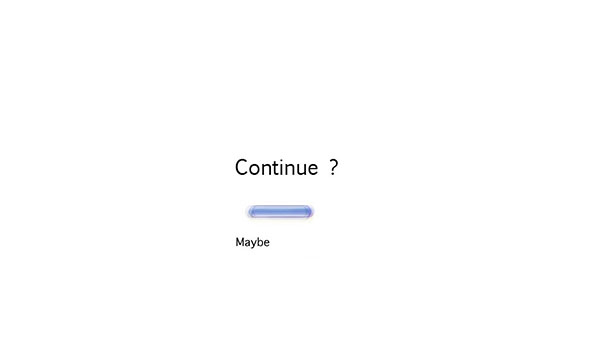

One of the crucial topics for Molleindustria was the precariousness of work, with all the ominous consequences that it implies. His first game was called Tamatipico (a ‘word game’ involving Tamagotchi and ‘atypical’ worker). It expresses how the atypical forms of work imply a centralized delirious and omnipresent control, and the complete submission to the system. The flexworker is completely controlled by the player that at the same time the player can identify himself with the exploited character. Time is accellerated, so the unfair balance of leisure and worktime is unbeareable, in a killing loop that is aimed only to maintain a brainless life, where watching TV is one of the most important source of happiness. This disturbing environment is also reflected in the next game, Tuboflex, where in 2010 a global Human Resource Services organization creates a system of tubes that instantly can relocate a temp worker. But here the instability of work leads to a more pessimistic conclusion. No chance to survive, the protagonist always ends as a beggar. This initial two games reflects the drama of dismantling the welfare and social rights through a the quick and colorful interaction of a videogame. The working conditions in the games become paradoxical but never surreal. Never losing the ‘sense’ of reality is one of the most important characteristic of Molleindustria work. In the McDonald’s videogame he’s unveiling the catastrophic consequences of global capital applied to food through a management simulation. McDonald is still a business giant with the attitude to skillfully move in the fast speed of the free market perfectly tuning with the games’ rules. Thus if it’s a game, metaphorically speaking, then the videogame is the ideal (non)place to represent its dynamics, letting the spectator/consumer to embody the relentless gears of the impressive fast food industry. McDonald’s videogame plays with a representation of its well known strategies, leaving to the player the taste, or better the disgust of playing with the McDonald’s own imposed rules. All the paradoxical stages of exploiting and the crossed responsibilities for the unavoidable continuos grow are monitored. Thus the simulation of management processes becomes a bulimic race against time that systematically squashes the player in the capital’s grip, leaving him alone with his own amount of bitter devastations. And this is perfectly matching the Molleindustria payoff, “radical games against the dictatorship of entertainment”.

2. Sex

If work is public exploitation, sex can be the new private territory for control. Among its early works, Molleindustria can sport an incredibly funny Orgasm Simulator, meant for women whose challenge is to successfully simulate an orgasm with the partner. Molleindustria stated that “videogames lack representation of sex. Maybe because in the videogames’ functionalist worlds everything is instrumental and nobody can justify a sexual intercourse”. But in ‘Queer Power‘ he takes things seriously, even a little bit educational, encouraging to simulate new situations and to explore a territory much larger than its commercial aspects. allowing to change one’s own sexual identity in real time to have a relationship with another person, also mutating, deconstructing the hetero/homo dichotomy so common in mass media. In ‘Queer Power’, the author tries to uncover the ‘denied identities’ of the player, with the help of a morphing silhouette which makes the identification process more natural and instinctive. In this subtle equilibrium between desire and representation, the player and its partner/adversary (a subversion of videogame roles typical of these authors) ‘win’ by reaching or giving an orgasm, and both things can happen at the same time. Or in the Molleindustria words “gaming is an essentially incorporeal practice where sex wouldn’t have any sense. Nevertheless, we have chosen to show it because we wanted to give the idea that sexual identity is a countinuous process defined by our choices and behaviors”.

3. Religion

In Italy religion is an unavoidable cultural limit. The Pope headquarters has historically and heavily influenced national politics and media, and the rules, silently and almost invisibly imposed by the catholic church, has been one of the biggest cultural influence in the country. In the earliest years Molleindustria played with the media influence wielded by the Pope John Paul 2nd public speeches. His Papaparolibero showed how he said “the combinatorial properties of software can be used to deconstruct the languages of power”. Even if Pope Wojtyla was dying then, Molleindustria strongly believed that ecclesiastical hierarchies already turned the suffering of Wojtyla into a strategic spectacle. And the religion spectacle is intertwined with its brand management, so no scandal or crime are allowed. That’s why Molleindustria latest effort was a cynical spirit and clearly controversial work. ‘Operation: Pedopriest‘ is translating into game rules the countless half-truth spread by the media about the paedophile activities pepretrated by priests. The player has to avoid the exposure of children abuses by priests, corrupting police or scaring the children’s parents. It’s probably the rudest game developed by Molleindustria, and the most radical of them all. There’s almost no fun here, and the cartoonish style assumes a dark meaning. The game was censored and put offline at least three times, especially after the public intervention of a really upset Catholic parliament deputy, that also lead to negative press. But Molleindustria faced a strong support by the Italian hacker community, through the registration of new fake domains and mirroring the game in various different hosts.

4. Memory

Power is strictly connected to collective memory, and for maintaining power is required to manipulate memory when required. Molleindustria is well aware of that, so playing with memory was also a priority for his cultural strategy. ‘Netparade‘ was a remarkable project in this sense. It was a digital representation of the Euro MayDay 2004, that allowed anyone to add his one profile, both in words and customizing his virtual alter-ego in the represented and animated demo. This way the real amount of people that would have been in the street is shown and an impressive total of 17.000 people placed their ‘avatar’ in the isometrically constructed virtual streets. Representation and collective presence make a statement about a place and a time that they want to remember in the future as a shared resource and opportunity to meet and make a piece of social history together. But history can be rewritten and then rapidly accredited by mass media. In ‘Memory Reloaded‘, Molleindustria dealt with danger of historical revisionism in contemporaneity, often too easily re-interpreting (and consequently re-writing) history. He finally let videogame play a role on historical memory preservation, with a brilliant combination of ‘memory’ as a classic card game and the collective memory transmutation while the player plays the game. He said “Unfortunately it is now necessary to consider history as a battleground, exactly as we do for the journalism. A battle in which the categories true and false don’t make any sense because the spectacular system is mobilized… If nobody start to criticize the myth of videogame “realism”, if nobody spread the ability to read the simulations, the so-called electronic entertainment will become the most sophisticated medium of propaganda”

Conclusions

“The ideology of a game resides in its rules” said Paolo ‘Molleindustria’, sublimating its pure ludologist approach. Still being very critical to the whole multiplayer online games scene, his works made clear statements through playful interaction, funny character and interface, all of them translated into campaign-like statements, embodying them in the true spirit of the game. But beyond the statements there’s a unique approach to social, ethical and human questions: they’re treated as popular subjects and effectively discussed through the game rules design, metaphorically writing the limit to the interaction. Videogame is then used as a legitimate medium, exploiting the limitelss distribution of the net and the emotional involvement of videogame, that potentially attract more interested persons. What’s the lesson we can learn from the young Molleindustria? First, again, that politics can be fun and that game rules can be used as a language, turning upside down the usual major companies propaganda. His style can become in the long term a paradigm, a scheme that can rapidly propagate ideologies, through a bunch of rules and funny characters amusing the player’s always available instincts.

[Bibliography]

Neural #22, Molleindustria interview

Carlo Climati, I giochi estremi dei giovani, Edizioni Paoline